Strolls with Pushkin by Andrei Sinyavsky

Russian Library

Rate this book

Andrei Sinyavsky wrote Strolls with Pushkin while confined to Dubrovlag, a Soviet labor camp, smuggling the pages out a few at a time to his wife. His irreverent portrait of Pushkin outraged emigres and Soviet scholars alike, yet his «disrespect» was meant only to rescue Pushkin from the stifling cult of personality that had risen up around him. Anglophone readers who question the longstanding adoration for Pushkin felt by generations of Russians will enjoy tagging along on Sinyavsky’s strolls with the great poet, discussing his life, fiction, and famously untranslatable poems. This new edition of Strolls with Pushkin also includes a later essay Sinyavsky wrote on the artist, «Journey to the River Black.»

304 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1975

About the author

a. k.a. Abram Tertz

k.a. Abram Tertz

Soviet dissident author. With co-defendant Yuli Daniel, the first defendant in a Soviet show trial to plead innocent.

What do you think?

Rate this book

Search review text

Displaying 1 — 9 of 9 reviews

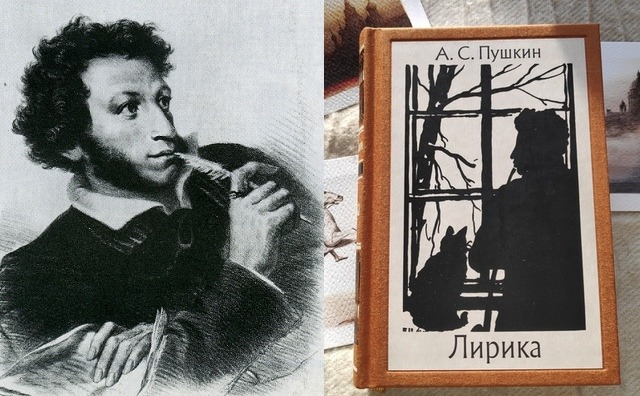

January 7, 2020By the middle of the last century, the official Soviet philology turned Alexander Pushkin into an idealized icon and sterile poetical dogma. But sooner or later dogmas start suffering from necrosis and Andrei Sinyavsky was the one who decided to fight this dead dogma so Strolls with Pushkin is a new approach to the poet’s oeuvre and his life.

…Nothing more

Will you squeeze out of my story

– that’s how Pushkin himself summed up the absence in his works of anything more than amusing anecdotes, elegantly and tastefully told. And perhaps we will find Pushkin easier to understand if we approach him not through the front hall, which is crammed with wreaths and busts that have an expression of uncompromising nobility on their brows, but rather with the help of the anecdotal caricatures of Pushkin that were sent back to the poet by the street, apparently in response to and in revenge for his great fame.

Infantility seems to have been one of Pushkin’s main features that ruled his behaviour throughout his entire life… So poetry and life to him were just a game… So it’s the source of his playful style… That’s why he has written so many tongue-in-cheek fairytales… So his poems were a device to win female hearts…

When you read Pushkin, you get the feeling that he has some bond with women, that he is at home with women – moreover as a specialist, one of those people you let into your house at all hours, someone indispensable, like a tailor, a hairdresser, a masseuse (she, after all, is a procuress, she, after all, is good at reading the cards), like a fashionable neurologist, a jeweler or a pet lapdog (so perky, with little curls…). You don’t have to stand on ceremony with a person like that, and every now and then you have to take him down a peg (You bastard! You upstart!), but you don’t kick him out, you don’t show him the door, you value him, you ask him for advice behind your mother-in-law’s back and sometimes you even suck up to him.

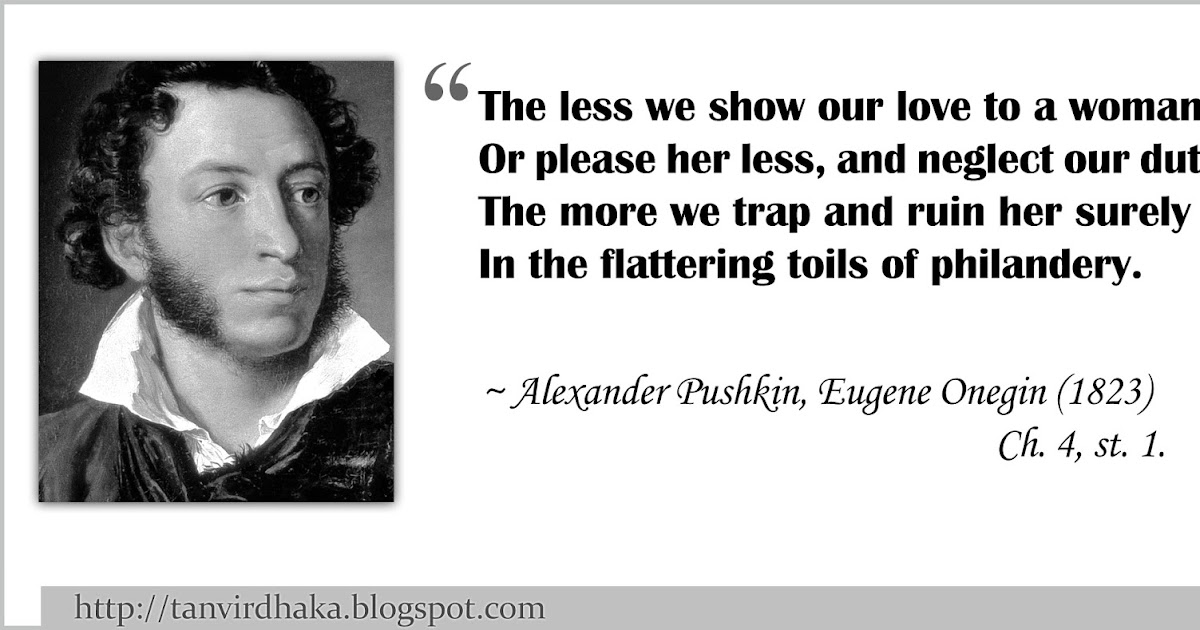

Writing Eugene Onegin he attempted to model the protagonist on himself and the result was a hollow aristocrat without any beliefs and convictions… He identified himself with Eugene Onegin but he ended up as Vladimir Lensky…

…With the accession of freedom everything became possible. The horizon swarmed with changes, and every object strove to stand upright, threatening at that very minute to turn world development in a different direction not as yet experienced by humanity. Conjectures of the sort “and what if Bonaparte had not caught a cold at the right time?” came into fashion. Pushkin, having the time of his life, played the solitaire of the so-called natural-historical process. If you drew the wrong queen, the whole picture would change irreparably. He was amused by this easy reversibility of events, which gave him food for thought and style. Galloping in the toe shoes of fate over the flagstones of the international forum, history, it seemed, was ready – for show, by bluffing – to replay its scenes from the beginning, to renew and change everything.Pushkin’s hands itched at the sight of such vacancies in the business of plot construction. In plain view, world-famous myths became overgrown with fresh stories, all ready to be set down on paper. Every louse aspired to become Napoleon. A little later and Raskolnikov would say: all is permitted! Everything was shaking. Everything was tottering on the brink of a conceptual abyss: and what if?! …the excessive hypotheticalness of being took your breath away.

Poetry is an echo of an era the poet lives in…

Caroline

765 reviews218 followers

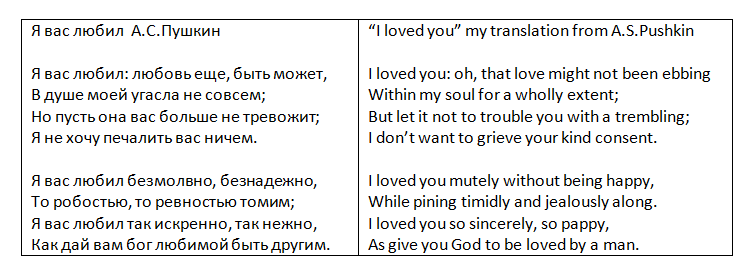

August 29, 2017Perhaps there is no poet who makes one feel the futility of translation as Pushkin does. Too often even a good translator can’t avoid the aura of camp or self-parody, and yet the flavor of greatness hovers around every line, evanescent and just out of reach. Sinyavsky argues that this is because Pushkin was indeed lighthearted, but perhaps always running to escape the great poet in himself.

I picked this up on a whim, thinking it would indeed be a stroll with Pushkin—light, puffing on cigars as we chat after dinner on a summer evening. Not exactly. This is serious literary criticism, meaning literary in itself and intricately argued criticism. But it is also seriously rewarding if one proceeds slowly. I proceeded very slowly, because I had only read

Sinyavsky is addressing both Pushkin directly, as an author, and his place in Russian literature and indeed in Russian existence. While he admires Pushkin, his aim is to expose the cult of the poet to a cold bath. Early on, following a brief summary of the poet’s life, he describes three commemorations: the 1899 centenary of Pushkin’s birth, the 84th anniversary of his death in 1921, and the 100th anniversary of his death in 1937.

Our memory preserves from infancy the cheerful name: Pushkin. This name, this sound fills up many days of our lives. The gloomy names of emperors, generals, inventors of weapons of murder, the torturers and martyrs of life. And next to them—this light name: Pushkin.Pushkin was able to carry his creative burden lightly and cheerfully despite the fact that the role of the poet is neither light nor cheerful; it is tragic.

And underlying much of the rest of the book is this underlying tragedy. Not in the simple sense of Pushkin’s early death in a duel, but in his relationship to his art and the persona he created to temporarily get out from under from the demands of that art.

In 1937, at the commemoration at the height of Stalin’s purges, Sinyavsky points out that the official line has totally co-opted the poet.

One gets the sense of Pushkin dancing furiously to entertain an audience, and writing his deceptively ‘simple’ poetry to do the same. Even while he was alive his works became iconic, with schoolboys memorizing works like The Bronze Horseman. But I was startled to read his poem To the Slanderers of Russia, defying the Western Europeans who criticized Russia for crushing the Polish rebellion in 1830. If Russians still memorize this, it certainly contributes to the fundamental tensions between Russia and the West.

Unfortunately I didn’t get to write this review when I finished Strolls and the poetry, so the points I wanted to make have faded a bit. But I highly recommend both. Despite the difficulty in getting his Russian into English, the poetry is still wonderful and essential to understanding Russian literary sensibility. (I chose the Arndt translation because it plunks for rhyme and meter; this may strain the meaning at times, but I thought it fit the spirit of the Sinyavsky analysis,

(I chose the Arndt translation because it plunks for rhyme and meter; this may strain the meaning at times, but I thought it fit the spirit of the Sinyavsky analysis,

Sinyavsky’s writing is not simple and quick to read, but I enjoyed the experience of working out his sentences. The translations by Catharine Theimer Nepomnyashchy and Slava I Yastremski are artful. Sinyavsky wrote this while incarcerated in the Dubrovlag labor camp, and smuggled it out in bits to his wife. He assembled and finished it after leaving the Soviet Union. The volume from Columbia University’s Russian Library includes excellent notes and a very helpful translation.

- literary-criticism russian

June 10, 2017

Лучшее, что когда-либо было написано о Пушкине. Не о далеком, запредельном солнце русской поэзии, которое намылило глаза школьникам, а о человеке, о поэте, о жизни.

«Я вам пишу — чего же боле? / Что я могу еще сказать?

Ничего она не может сказать, одним рывком отворяя себя в сбивчивых ламентациях, смысл которых — если подходить к ним с буквальной меркой ее пустого романа с Онегиным — сводится к двум приблизительно, довольно типичным и тривиальным идеям: 1) «теперь ты будешь меня презирать» и 2) «а души ты моей все-таки не познал». Но как они сказаны!..»

Но как они сказаны!..»

«Вселенский замах не мешал ему при каждом шаге отдавать предпочтение расположенной под боком букашке. «

«Болтовня предполагала при общей светскости тона заведомое снижение речи в сферу частного быта, который таким способом вытаскивается на свет со всяким домашним хламом и житейской дребеденью. Отсюда и происходил реализм. Но та же болтовня исключала сколько-нибудь серьезное и длительное знакомство с действительностью, от которой автор отделывался комплиментами и, рассылая на ходу воздушные поцелуи, мчался да��ьше давить мух. С пушкинского реализма не спросишь: а где тут у вас показано крепостное право? и куда вы подевали знаменитую 10-ую главу из «Евгения Онегина?» Он всегда отговорится: да я пошутил.»

«Скольких людей мы помним и любим только за то, что их угораздило жить неподалеку от Пушкина. И достойных, кто сами с усами — Кюхельбекера например, знаменитого главным образом тем, что Пушкин однажды, объевшись, почувствовал себя «кюхельбекерно». Теперь хоть лезь на Сенатскую площадь, хоть пиши трагедию — ничто не поможет: навсегда припечатали: кюхельбекерно.»

Теперь хоть лезь на Сенатскую площадь, хоть пиши трагедию — ничто не поможет: навсегда припечатали: кюхельбекерно.»

Atreju

178 reviews4 followers

August 29, 2021127 furono le lettere scritte dall’autore alla moglie durante gli anni di gulag in un lager della Mordovia. In queste 127 lettere Sinjavskij ha inserito i frammenti che compongono le sue «passeggiate» letterarie, cioè le sue riflessioni sulla figura e sull’opera del sommo poeta russo. Non si tratta di un testo di critica letteraria ma di «prosa lirica», come è stato a più riprese affermato. Divagazioni e meditazioni scaturite dalla prigionia e dalla condizione imposta dai lavori forzati. Il tutto, ha un tono molto leggero e godibile perché si avverte tra le righe l’anima dell’autore. Non certo è un esercizio di sterile erudizione, semmai un manifesto della libertà creativa.

Ottimo anche il breve saggio del curatore Sergio Rapetti sulla figura di Sinjavskij, intitolato «Il soffio della poesia, per poter respirare e vivere». Illumina davvero il testo dando la giusta inquadratura al suo autore.

Illumina davvero il testo dando la giusta inquadratura al suo autore.

Josh

89 reviews62 followers

February 6, 2008Almost as good as Voices from the Chorus, and maybe more enjoyable. Basically, Tertz expands the prision to include all of Russia, and renames the warden Fate. Never really thought about Fate, or took it seriously, until I read this book. Absolute confinement as absolute freedom — but again, Tertz shows you how it’s done, rather than just describing the process abstractly.

December 21, 2017

Strolls with Pushkin – one of the most controversial books published during the glasnost period – is wonderfully readable, even if you are not steeped in Pushkinian erudition. In a brilliant display of intellectual and linguistic gymnastics, Sinyavsky takes on the cult of personality enveloping the man who represents the Russian soul.

Reviewed on The BookBlast® Diary 2017

- reviewed-by-bookblast

September 8, 2021

Ok, I didn’t quite finish this book but it was interesting. Can see how it must be shocking for Pushkin-lovers of all ages.

Can see how it must be shocking for Pushkin-lovers of all ages.

Displaying 1 — 9 of 9 reviews

NABOKV-L post 0027625, Wed, 20 Dec 2017 14:25:56 +0300

In VN’s novel Pale Fire (1962) John Shade wrote his poem in July of 1959. According to Kinbote (Shade’s commentator who imagines that he is Charles the Beloved, the last self-exiled king of Zembla), the poem was begun at the dead center of the year:

The poem was begun at the dead center of the year, a few minutes after midnight July 1, while I played chess with a young Iranian enrolled in our summer school; and I do not doubt that our poet would have understood his annotator’s temptations to synchronize a certain fateful fact, the departure from Zembla of the would-be regicide Gradus, with that date. Actually, Gradus left Onhava on the Copenhagen plane on July 5. (note to Lines 1-4)

In the poem’s first line Shade compares himself to the shadow of the waxwing (a bird of the genus Bombycilla). In his story Strashnaya mest’ (“A Terrible Vengeance,” 1832) Gogol says that a rare bird can fly to the middle of the Dnepr. Vladimir I (958-1015), a Grand Prince of Kiev who converted to Christianity in 988, caused the effigy of Perun (the Slavic god of thunder) to be drowned in the Dnepr. Perun brings to mind Pern, “the Devil” in Zemblan:

In his story Strashnaya mest’ (“A Terrible Vengeance,” 1832) Gogol says that a rare bird can fly to the middle of the Dnepr. Vladimir I (958-1015), a Grand Prince of Kiev who converted to Christianity in 988, caused the effigy of Perun (the Slavic god of thunder) to be drowned in the Dnepr. Perun brings to mind Pern, “the Devil” in Zemblan:

Many years ago—how many I would not care to say—I remember my Zemblan nurse telling me, a little man of six in the throes of adult insomnia: «Minnamin, Gut mag alkan, Pern dirstan» (my darling, God makes hungry, the Devil thirsty). Well, folks, I guess many in this fine hall are as hungry and thirsty as me, and I’d better stop, folks, right here.

Yes, better stop. My notes and self are petering out. Gentlemen, I have suffered very much, and more than any of you can imagine. I pray for the Lord’s benediction to rest on my wretched countrymen. My work is finished. My poet is dead. (note to Line 1000)

Minnamin and Kinbote’s sufferings bring to mind Mignon’s song in Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre (“Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship,” 1796):

Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt

Weiß, was ich leide!

Allein und abgetrennt

Von aller Freude,

Seh ich ans Firmament

Nach jener Seite.

Ach! der mich liebt und kennt,

Ist in der Weite.

Es schwindelt mir, es brennt

Mein Eingeweide.

Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt

Weiß, was ich leide!

Only those who know longing

Know how I suffer!

Alone and separated

From all joy,

I behold the firmament

From yonder side.

Ah! the one who loves and knows me

Is in the vast unknown.

It dizzies me, it burns

my guts.

Only those who know longing

Know how I suffer!

In his Russian version of Mignon’s song, Net, tol’ko tot, kto znal (“No, only he who knew…” 1858), Lev Mei changed the girl’s sex:

Нет, только тот, кто знал

Свиданья жажду,

Поймёт, как я страдал

И как я стражду.

Гляжу я вдаль… нет сил,

Тускнеет око…

Ах, кто меня любил

И знал — далёко!

Вся грудь горит… Кто знал

Свиданья жажду,

Поймёт, как я страдал

И как я стражду.

In Mei’s poem strazhdu (“I suffer”) rhymes with zhazhdu (Acc. of zhazhda, “thirst”). Mei’s poem was set to music by Tchaikovsky, the composer who died of cholera after drinking a glass of unboiled water. In a letter of Nov. 18, 1831, to Yazykov Pushkin quotes the epistle that Khvostov wrote to him:

of zhazhda, “thirst”). Mei’s poem was set to music by Tchaikovsky, the composer who died of cholera after drinking a glass of unboiled water. In a letter of Nov. 18, 1831, to Yazykov Pushkin quotes the epistle that Khvostov wrote to him:

Хвостов написал мне послание, где он помолодел и тряхнул стариной. Он говорит:

Приближася похода к знаку,

Я стал союзник Зодиаку;

Холеры не любя пилюль,

Я пел при старости июль

Drawing near the sign of campaign,

I became an ally of the Zodiac;

Not loving the pills of cholera,

In my old age I sang of July, etc.

и проч. в том же виде. Собираюсь достойно отвечать союзнику Водолея, Рака и Козерога. В прочем всё у нас благополучно.

In his Ode to His Excellency Count Dm. Iv. Khvostov (1825) Pushkin compares Khvostov to Byron (the poet who died in 1824 and whose “famous shade” is mentioned by Pushkin):

Вам с Бейроном шипела злоба,

Гремела и правдива лесть.

Он лорд — граф ты! Поэты оба!

Се, мнится, явно сходство есть.

Spite hissed to you and Byron,

Truthful flattery also thundered.

He is a Lord, you are a Count! Both are poets!

Thus, an obvious resemblance seems to be.

The name Khvostov comes from khvost (tail). Oda (“ode” in Russian) rhymes with coda (Italian for “tail”). It seems that, to be completed, Shade’s poem needs not only Line 1000 (identical to Line 1: “I was the shadow of the waxwing slain”), but, like some sonnets, also a coda (Line 1001: “By its own double in the windowpane”). The total number of lines in the finished version of Shade’s poem bring to mind One Thousand and One Nights, also known as The Arabian Nights. In a letter of Dec. 1, 1826, to Alekseev Pushkin calls his Kishinev friend otshel’nik Bessarabskiy (“the Bessarabian hermit”) and asks Alekseev to gladden him not with an Arabian fairy tale, but with Alekseev’s Russian truth. In a letter of Apr. 30, 1823, to Alexander Turgenev Vyazemski calls Pushkin bes arabskiy (the Arabian devil), a pun on Bessarabskiy (the Bessarabian).

In a letter of Nov. 25, 1892, to Suvorin Chekhov (the author of Rara Avis, 1886) says that Byron was as smart as a hundred devils:

Ну-с, теперь об уме. Григорович думает, что ум может пересилить талант. Байрон был умён, как сто чертей, однако же талант его уцелел. Если мне скажут, что Икс понёс чепуху оттого, что ум у него пересилил талант, или наоборот, то я скажу: это значит, что у Икса не было ни ума, ни таланта.

And now as to intellect, Sir Grigorovich thinks that intellect can overwhelm talent. Byron was as smart as a hundred devils; nevertheless, his talent has survived intact. If we say that X talked nonsense because his intellect overwhelmed his talent or vice versa, then I say X had neither brains nor talent.

Grigorovich is the author of Guttapercevyi mal’chik (“The Gutta-Percha Boy,” 1883), a novella alluded to by Chekhov in the same letter of Nov. 25, 1892, to Suvorin:

Вас нетрудно понять, и Вы напрасно браните себя за то, что неясно выражаетесь. Вы горький пьяница, а я угостил Вас сладким лимонадом, и Вы, отдавая должное лимонаду, справедливо замечаете, что в нём нет спирта. В наших произведениях нет именно алкоголя, который бы пьянил и порабощал, и это Вы хорошо даете понять. Отчего нет? Оставляя в стороне «Палату № 6» и меня самого, будем говорить вообще, ибо это интересней. Будем говорить об общих причинах, коли Вам не скучно, и давайте захватим целую эпоху. Скажите по совести, кто из моих сверстников, т. е. людей в возрасте 30 — 45 лет дал миру хотя одну каплю алкоголя? Разве Короленко, Надсон и все нынешние драматурги не лимонад? Разве картины Репина или Шишкина кружили Вам голову? Мило, талантливо, Вы восхищаетесь и в то же время никак не можете забыть, что Вам хочется курить. Наука и техника переживают теперь великое время, для нашего же брата это время рыхлое, кислое, скучное, сами мы кислы и скучны, умеем рождать только гуттаперчевых мальчиков, и не видит этого только Стасов, которому природа дала редкую способность пьянеть даже от помоев.

Вы горький пьяница, а я угостил Вас сладким лимонадом, и Вы, отдавая должное лимонаду, справедливо замечаете, что в нём нет спирта. В наших произведениях нет именно алкоголя, который бы пьянил и порабощал, и это Вы хорошо даете понять. Отчего нет? Оставляя в стороне «Палату № 6» и меня самого, будем говорить вообще, ибо это интересней. Будем говорить об общих причинах, коли Вам не скучно, и давайте захватим целую эпоху. Скажите по совести, кто из моих сверстников, т. е. людей в возрасте 30 — 45 лет дал миру хотя одну каплю алкоголя? Разве Короленко, Надсон и все нынешние драматурги не лимонад? Разве картины Репина или Шишкина кружили Вам голову? Мило, талантливо, Вы восхищаетесь и в то же время никак не можете забыть, что Вам хочется курить. Наука и техника переживают теперь великое время, для нашего же брата это время рыхлое, кислое, скучное, сами мы кислы и скучны, умеем рождать только гуттаперчевых мальчиков, и не видит этого только Стасов, которому природа дала редкую способность пьянеть даже от помоев. Причины тут не в глупости нашей, не в бездарности и не в наглости, как думает Буренин, а в болезни, которая для художника хуже сифилиса и полового истощения. У нас нет «чего-то», это справедливо, и это значит, что поднимите подол нашей музе, и Вы увидите там плоское место. Вспомните, что писатели, которых мы называем вечными или просто хорошими и которые пьянят нас, имеют один общий и весьма важный признак: они куда-то идут и Вас зовут туда же, и Вы чувствуете не умом, а всем своим существом, что у них есть какая-то цель, как у тени отца Гамлета, которая недаром приходила и тревожила воображение. У одних, смотря по калибру, цели ближайшие — крепостное право, освобождение родины, политика, красота или просто водка, как у Дениса Давыдова, у других цели отдаленные — бог, загробная жизнь, счастье человечества и т. п. Лучшие из них реальны и пишут жизнь такою, какая она есть, но оттого, что каждая строчка пропитана, как соком, сознанием цели, Вы, кроме жизни, какая есть, чувствуете еще ту жизнь, какая должна быть, и это пленяет Вас.

Причины тут не в глупости нашей, не в бездарности и не в наглости, как думает Буренин, а в болезни, которая для художника хуже сифилиса и полового истощения. У нас нет «чего-то», это справедливо, и это значит, что поднимите подол нашей музе, и Вы увидите там плоское место. Вспомните, что писатели, которых мы называем вечными или просто хорошими и которые пьянят нас, имеют один общий и весьма важный признак: они куда-то идут и Вас зовут туда же, и Вы чувствуете не умом, а всем своим существом, что у них есть какая-то цель, как у тени отца Гамлета, которая недаром приходила и тревожила воображение. У одних, смотря по калибру, цели ближайшие — крепостное право, освобождение родины, политика, красота или просто водка, как у Дениса Давыдова, у других цели отдаленные — бог, загробная жизнь, счастье человечества и т. п. Лучшие из них реальны и пишут жизнь такою, какая она есть, но оттого, что каждая строчка пропитана, как соком, сознанием цели, Вы, кроме жизни, какая есть, чувствуете еще ту жизнь, какая должна быть, и это пленяет Вас.

It is easy to understand you, and there is no need for you to abuse yourself for obscurity of expression. You are a hard drinker, and I have regaled you with sweet lemonade, and you, after giving the lemonade its due, justly observe that there is no spirit in it. That is just what is lacking in our productions — the alcohol which could intoxicate and subjugate, and you state that very well. Why not? Putting aside “Ward No. 6” and myself, let us discuss the matter in general, for that is more interesting. Let ms discuss the general causes, if that won’t bore you, and let us include the whole age. Tell me honestly, who of my contemporaries — that is, men between thirty and forty-five — have given the world one single drop of alcohol? Are not Korolenko, Nadson, and all the playwrights of to-day, lemonade? Have Repin’s or Shishkin’s pictures turned your head? Charming, talented, you are enthusiastic; but at the same time you can’t forget that you want to smoke. Science and technical knowledge are passing through a great period now, but for our sort it is a flabby, stale, and dull time. We are stale and dull ourselves, we can only beget gutta-percha boys, and the only person who does not see that is Stasov, to whom nature has given a rare faculty for getting drunk on slops. The causes of this are not to be found in our stupidity, our lack of talent, or our insolence, as Burenin imagines, but in a disease which for the artist is worse than syphilis or sexual exhaustion. We lack “something,” that is true, and that means that, lift the robe of our muse, and you will find within an empty void. Let me remind you that the writers, who we say are for all time or are simply good, and who intoxicate us, have one common and very important characteristic; they are going towards something and are summoning you towards it, too, and you feel not with your mind, but with your whole being, that they have some object, just like the ghost of Hamlet’s father, who did not come and disturb the imagination for nothing. Some have more immediate objects — the abolition of serfdom, the liberation of their country, politics, beauty, or simply vodka, like Denis Davydov; others have remote objects — God, life beyond the grave, the happiness of humanity, and so on.

We are stale and dull ourselves, we can only beget gutta-percha boys, and the only person who does not see that is Stasov, to whom nature has given a rare faculty for getting drunk on slops. The causes of this are not to be found in our stupidity, our lack of talent, or our insolence, as Burenin imagines, but in a disease which for the artist is worse than syphilis or sexual exhaustion. We lack “something,” that is true, and that means that, lift the robe of our muse, and you will find within an empty void. Let me remind you that the writers, who we say are for all time or are simply good, and who intoxicate us, have one common and very important characteristic; they are going towards something and are summoning you towards it, too, and you feel not with your mind, but with your whole being, that they have some object, just like the ghost of Hamlet’s father, who did not come and disturb the imagination for nothing. Some have more immediate objects — the abolition of serfdom, the liberation of their country, politics, beauty, or simply vodka, like Denis Davydov; others have remote objects — God, life beyond the grave, the happiness of humanity, and so on. The best of them are realists and paint life as it is, but, through every line’s being soaked in the consciousness of an object, you feel, besides life as it is, the life which ought to be, and that captivates you.

The best of them are realists and paint life as it is, but, through every line’s being soaked in the consciousness of an object, you feel, besides life as it is, the life which ought to be, and that captivates you.

Zemblan for “God,” Gut seems to hint not only at Gott (“God” in German), but also at the gutta-percha boys mentioned by Chekhov. A young acrobat, the gutta-percha boy in Grigorovich’s story brings to mind the circus artists mentioned by Kinbote in his Commentary:

She [Queen Disa] had recently lost both parents and had no real friend to turn to for explanation and advice when the inevitable rumors reached her; these she was too proud to discuss with her ladies in waiting but she read books, found out all about our manly Zemblan customs, and concealed her naive distress under a great show of sarcastic sophistication. He congratulated her on her attitude, solemnly swearing that he had given up, or at least would give up, the practice of his youth; but everywhere along the road powerful temptations stood at attention. He succumbed to them from time to time, then every other day, then several times daily—especially during the robust regime of Harfar Baron of Shalksbore, a phenomenally endowed young brute (whose family name, «knave’s farm,» is the most probably derivation of «Shakespeare»). Curdy Buff—as Harfar was nicknamed by his admirers—had a huge escort of acrobats and bareback riders, and the whole affair rather got out of hand so that Disa, upon unexpectedly returning from a trip to Sweden, found the Palace transformed into a circus. He again promised, again fell, and despite the utmost discretion was again caught. At last she removed to the Riviera leaving him to amuse himself with a band of Eton-collared, sweet-voices minions imported from England. (note to Line 433)

He succumbed to them from time to time, then every other day, then several times daily—especially during the robust regime of Harfar Baron of Shalksbore, a phenomenally endowed young brute (whose family name, «knave’s farm,» is the most probably derivation of «Shakespeare»). Curdy Buff—as Harfar was nicknamed by his admirers—had a huge escort of acrobats and bareback riders, and the whole affair rather got out of hand so that Disa, upon unexpectedly returning from a trip to Sweden, found the Palace transformed into a circus. He again promised, again fell, and despite the utmost discretion was again caught. At last she removed to the Riviera leaving him to amuse himself with a band of Eton-collared, sweet-voices minions imported from England. (note to Line 433)

In a letter of Apr. 26, 1835, to Dmitriev Pushkin calls Count Uvarov, the minister of education, fokusnik (a conjurer) and Dondukov-Korsakov, whose homosexual relationship with Uvarov Pushkin ridicules in his epigram V akademii nauk… (“In the Academy of sciences…” 1835), ego payas (his clown):

На академии наши нашёл чёрный год: едва в Российской почил Соколов, как в академии наук явился вице-президентом Дондуков-Корсаков. Уваров фокусник, а Дондуков-Корсаков его паяс. Кто-то сказал, что куда один, туда и другой: один кувыркается на канате, а другой под ним на полу.

Уваров фокусник, а Дондуков-Корсаков его паяс. Кто-то сказал, что куда один, туда и другой: один кувыркается на канате, а другой под ним на полу.

In his Foreword to Shade’s poem Kinbote describes his favorite photograph of Shade and compares Shade to a conjurer:

I have one favorite photograph of him. In this color snapshot taken by a onetime friend of mine, on a brilliant spring day, Shade is seen leaning on a sturdy cane that had belonged to his aunt Maud (see line 86 <http://www.shannonrchamberlain.com/palefirepoem.html#line86> ). I am wearing a white windbreaker acquired in a local sports shop and a pair of lilac slacks hailing from Cannes. My left hand is half raised—not to pat Shade on the shoulder as seems to be the intention, but to remove my sunglasses which, however, it never reached in that life, the life of the picture; and the library book under my right arm is a treatise on certain Zemblan calisthenics in which I proposed to interest that young roomer of mine who snapped the picture. A week later he was to betray my trust by taking sordid advantage of my absence on a trip to Washington whence I returned to find that he had been entertaining a fiery-haired whore from Exton who had left her combings and reek in all three bathrooms. Naturally, we separated at once, and through a chink in the window curtains I saw bad Bob standing rather pathetically, with his crewcut, and shabby valise, and the skis I had given him, all forlorn on the roadside, waiting for a fellow student to drive him away forever. I can forgive everything save treason.

A week later he was to betray my trust by taking sordid advantage of my absence on a trip to Washington whence I returned to find that he had been entertaining a fiery-haired whore from Exton who had left her combings and reek in all three bathrooms. Naturally, we separated at once, and through a chink in the window curtains I saw bad Bob standing rather pathetically, with his crewcut, and shabby valise, and the skis I had given him, all forlorn on the roadside, waiting for a fellow student to drive him away forever. I can forgive everything save treason.

We never discussed, John Shade and I, any of my personal misfortunes. Our close friendship was on that higher, exclusively intellectual level where one can rest from emotional troubles, not share them. My admiration for him was for me a sort of alpine cure. I experienced a grand sense of wonder whenever I looked at him, especially in the presence of other people, inferior people. This wonder was enhanced by my awareness of their not feeling what I felt, of their not seeing what I saw, of their taking Shade for granted, instead of drenching every nerve, so to speak, in the romance of his presence. Here he is, I would say to myself, that is his head, containing a brain of a different brand than that of the synthetic jellies preserved in the skulls around him. He is looking from the terrace (of Prof. C.’s house on that March evening) at the distant lake. I am looking at him. I am witnessing a unique physiological phenomenon: John Shade perceiving and transforming the world, taking it in and taking it apart, re-combining its elements in the very process of storing them up so as to produce at some unspecified date an organic miracle, a fusion of image and music, a line of verse. And I experienced the same thrill as when in my early boyhood I once watched across the tea table in my uncle’s castle a conjurer who had just given a fantastic performance and was now quietly consuming a vanilla ice. I stared at his powdered cheeks, at the magical flower in his buttonhole where it had passed through a succession of different colors and had now become fixed as a white carnation, and especially at his marvelous fluid-looking fingers which could if he chose make his plate into a dove by tossing up in the air.

Here he is, I would say to myself, that is his head, containing a brain of a different brand than that of the synthetic jellies preserved in the skulls around him. He is looking from the terrace (of Prof. C.’s house on that March evening) at the distant lake. I am looking at him. I am witnessing a unique physiological phenomenon: John Shade perceiving and transforming the world, taking it in and taking it apart, re-combining its elements in the very process of storing them up so as to produce at some unspecified date an organic miracle, a fusion of image and music, a line of verse. And I experienced the same thrill as when in my early boyhood I once watched across the tea table in my uncle’s castle a conjurer who had just given a fantastic performance and was now quietly consuming a vanilla ice. I stared at his powdered cheeks, at the magical flower in his buttonhole where it had passed through a succession of different colors and had now become fixed as a white carnation, and especially at his marvelous fluid-looking fingers which could if he chose make his plate into a dove by tossing up in the air.

At the end of his Commentary Kinbote (whom one is tempted to compare to Shade’s clown) mentions a million of photographers:

But whatever happens, wherever the scene is laid, somebody, somewhere, will quietly set out—somebody has already set out, somebody still rather far away is buying a ticket, is boarding a bus, a ship, a plane, has landed, is walking toward a million photographers, and presently he will ring at my door—a bigger, more respectable, more competent Gradus. (note to Line 1000)

In Chapter Two (XIV) of Eugene Onegin Pushkin mentions dvunogikh tvarey milliony (the millions of two-legged creatures) who are for us orudie odno (only tools). There is dno (“bottom”) in odno (neut. of odin, “one”). Odno = Odon (world-famous actor and Zemblan patriot) = Nodo (Odon’s half-brother, a cardsharp and despicable traitor). In his essay Pouchkine ou le vrai et le vraisemblable (1937) VN points out that, had Pushkin lived a couple of years longer, we would have had his photograph. Kinbote completes his work on Shade’s poem and commits suicide on Oct. 19, 1959, the anniversary of Pushkin’s Lyceum. Shade’s, Kinbote’s and Gradus’ “real” name seems to be Botkin. An American scholar of Russian descent, Professor Vsevolod Botkin went mad and became Shade, Kinbote and Gradus after the tragic death of his daughter Nadezhda (Hazel Shade of Kinbote’s Commentary). There is nadezhda (a hope) that, after Kinbote’s suicide, Botkin, like Count Vorontsov (another target of Pushkin’s epigrams, “half-milord, half-merchant, etc.”), will be full again.

Kinbote completes his work on Shade’s poem and commits suicide on Oct. 19, 1959, the anniversary of Pushkin’s Lyceum. Shade’s, Kinbote’s and Gradus’ “real” name seems to be Botkin. An American scholar of Russian descent, Professor Vsevolod Botkin went mad and became Shade, Kinbote and Gradus after the tragic death of his daughter Nadezhda (Hazel Shade of Kinbote’s Commentary). There is nadezhda (a hope) that, after Kinbote’s suicide, Botkin, like Count Vorontsov (another target of Pushkin’s epigrams, “half-milord, half-merchant, etc.”), will be full again.

Here is an improved version of the anagram in my previous post (“London, Lute, kvaka sesva, Avenue Guillaume Pitt & Chose University in Ada”):

Sekvana + Moskva + revolt = kvaka sesva + Lermontov

Sekvana – Sequana (the Latin name of the Seine, a river that flows throw Paris) in Russian spelling; in his epistle to Vasiliy Pushkin (a minor poet, uncle of Alexander Pushkin) Count Khvostov pairs Sekvana with the Thames and, in one of the next lines, mentions the Volga; “the Volga region and similar watersheds” are mentioned by Van Veen in the chapter dedicated to his novel Letters from Terra (2. 2)

2)

Moskva – Moscow; the Moskva river that flows through Moscow

revolt – in “History of Pugachov” (1834) Pushkin says: ‘God save us from seeing a Russian revolt, senseless and merciless.

kvaka sesva – quoi que ce soit (whatever it might be) in Marina’s mispronunciation

In “The Demon” (1840) Lermontov compares Mount Kazbek to gran’ almaza (a diamond’s facet). As a child, Van “puzzled out the exaggerated but, on the whole, complimentary allusions to his father’s volitations and loves in another life in Lermontov’s diamond-faceted tetrameters” (1.28). The lines in “The Demon” are paraphrased by Van in the chapter in which speaks of his father’s death:

He greeted the dawn of a placid and prosperous century (more than half of which Ada and I have now seen) with the beginning of his second philosophic fable, a ‘denunciation of space’ (never to be completed, but forming in rear vision, a preface to his Texture of Time). Part of that treatise, a rather mannered affair, but nasty and sound, appeared in the first issue (January, 1904) of a now famous American monthly, The Artisan, and a comment on the excerpt is preserved in one of the tragically formal letters (all destroyed save this one) that his sister sent him by public post now and then. Somehow, after the interchange occasioned by Lucette’s death such nonclandestine correspondence had been established with the tacit sanction of Demon:

Somehow, after the interchange occasioned by Lucette’s death such nonclandestine correspondence had been established with the tacit sanction of Demon:

And o’er the summits of the Tacit

He, banned from Paradise, flew on:

Beneath him, like a brilliant’s facet,

Mount Peck with snows eternal shone. (3.7)

On Ada’s sixteenth birthday Demon wants to give her une rivière de diamants. Marina objects to Demon giving kvaka sesva to his daughter.

Lermontov’s poem Borodino (1837) begins as follows:

“Скажи-ка, дядя, ведь не даром

Москва, спалённая пожаром,

Французу отдана.

Ведь были ж схватки боевые,

Да, говорят, ещё какие!

Недаром помнит вся Россия

Про день Бородина!»

«Tell me now, uncle, not in vain,

after all, was flame bound Moscow

Given over to the French.

For there were surges of battle,

They say, and were there ever!

Not in vain does all Russia remember

The day at Borodino!»

Describing the Night of the Burning Barn (when he and Ada make love for the first time), Van mentions Mlle Stopchin (a representative of Mme de Ségur, née Rostopchine, author of Les Malheurs de Sophie) and Mlle Larivière (Lucette’s governess):

A sort of hoary riddle (Les Sophismes de Sophie by Mlle Stopchin in the Bibliothèque Vieux Rose series): did the Burning Barn come before the Cockloft or the Cockloft come first. Oh, first! We had long been kissing cousins when the fire started. In fact, I was getting some Château Baignet cold cream from Ladore for my poor chapped lips. And we both were roused in our separate rooms by her crying au feu! July 28? August 4?

Oh, first! We had long been kissing cousins when the fire started. In fact, I was getting some Château Baignet cold cream from Ladore for my poor chapped lips. And we both were roused in our separate rooms by her crying au feu! July 28? August 4?

Who cried? Stopchin cried? Larivière cried? Larivière? Answer! Crying that the barn flambait? (1.19)

The Great Moscow Fire of 1812 started thanks to Rostopchin’s orders (the governor of Moscow, Count Rostopchin was the father of Mme de Ségur). The Baronial Barn near Ardis Hall was set on fire by Kim Beauharnais (the kitchen boy and photographer at Ardis who was bribed by Ada). Josephine Beauharnais (known on Antiterra as Queen Josephine, 1.5) was Napoleon’s first wife.

Alexey Sklyarenko

Search archive with Google:

http://www.google.com/advanced_search?q=site:listserv.ucsb.edu&HL=en

Contact the Editors: mailto:[email protected],[email protected],[email protected]

Zembla: http://www.libraries. psu.edu/nabokov/zembla.htm

psu.edu/nabokov/zembla.htm

Nabokov Studies: https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/257

Chercheurs Enchantes: http://www.vladimir-nabokov.org/association/chercheurs-enchantes/73

Nabokv-L policies: http://web.utk.edu/~sblackwe/EDNote.htm

Nabokov Online Journal:» http://www.nabokovonline.com

AdaOnline: «http://www.ada.auckland.ac.nz/

The Nabokov Society of Japan’s Annotations to Ada: http://vnjapan.org/main/ada/index.html

The VN Bibliography Blog: http://vnbiblio.com/

Search the archive with L-Soft: https://listserv.ucsb.edu/lsv-cgi-bin/wa?A0=NABOKV-L

Manage subscription options :http://listserv.ucsb.edu/lsv-cgi-bin/wa?SUBED1=NABOKV-L

Четкое письмо | Мой любимый рассказ: Капитанская дочка Александра Пушкина

Писателей и редакторов часто просят назвать их любимый роман, но редко просят назвать любимый рассказ. Этот факт может быть обусловлен краткостью рассказа и тем, что «совершенных» рассказов намного больше, чем «совершенных» романов. Опять же, романы не обязательно называют «идеальными», а скорее просто «великими», и общепризнано, что величие не исключает наличия недостатков. Несмотря на все это, «фаворит» подразумевает субъективную точку зрения; и все же я думаю, что для большинства читателей трудно выбрать один короткий рассказ, который будет жить в их памяти больше, чем все остальные. Но на самом деле у меня есть самый любимый рассказ, единственный короткий рассказ, который я постоянно и ритуально перечитываю примерно раз в год. это Капитанская дочка Александр Пушкин.

Опять же, романы не обязательно называют «идеальными», а скорее просто «великими», и общепризнано, что величие не исключает наличия недостатков. Несмотря на все это, «фаворит» подразумевает субъективную точку зрения; и все же я думаю, что для большинства читателей трудно выбрать один короткий рассказ, который будет жить в их памяти больше, чем все остальные. Но на самом деле у меня есть самый любимый рассказ, единственный короткий рассказ, который я постоянно и ритуально перечитываю примерно раз в год. это Капитанская дочка Александр Пушкин.

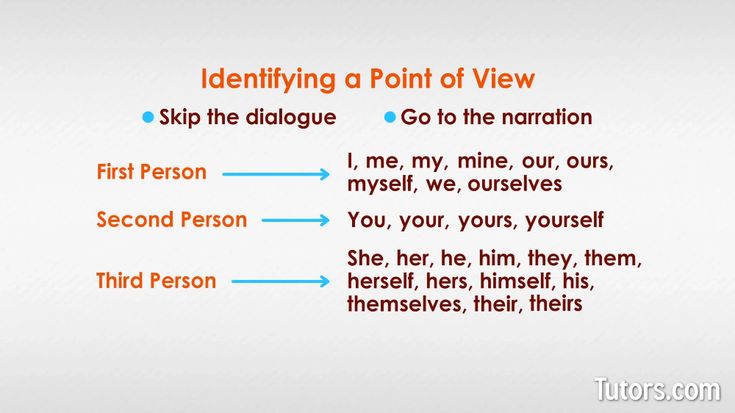

Это довольно длинная короткая история, действие которой происходит в России 19 го века, рассказанная от лица Петра, семнадцатилетнего мальчика, которого отец отправляет в военный полк. По пути на военную службу Петр дружит с человеком, которого он встречает позже, возглавляя группу мятежных солдат, которые захватывают форт, где находится Петр. В конце концов бунтовщик казнит всех бойцов полка Петра, но сохраняет жизнь молодому солдату.

Во время службы в полку Петр влюбляется в Машу, дочь трактирщика, и решает жениться на ней. Но поскольку его жизнь была сохранена, когда лидер повстанцев позже был пойман и казнен, Петра подозревают в предательстве святой Руси и заключают в тюрьму. Затем его возлюбленная Маша едет в Санкт-Петербург, чтобы ходатайствовать перед Екатериной Великой о его освобождении.

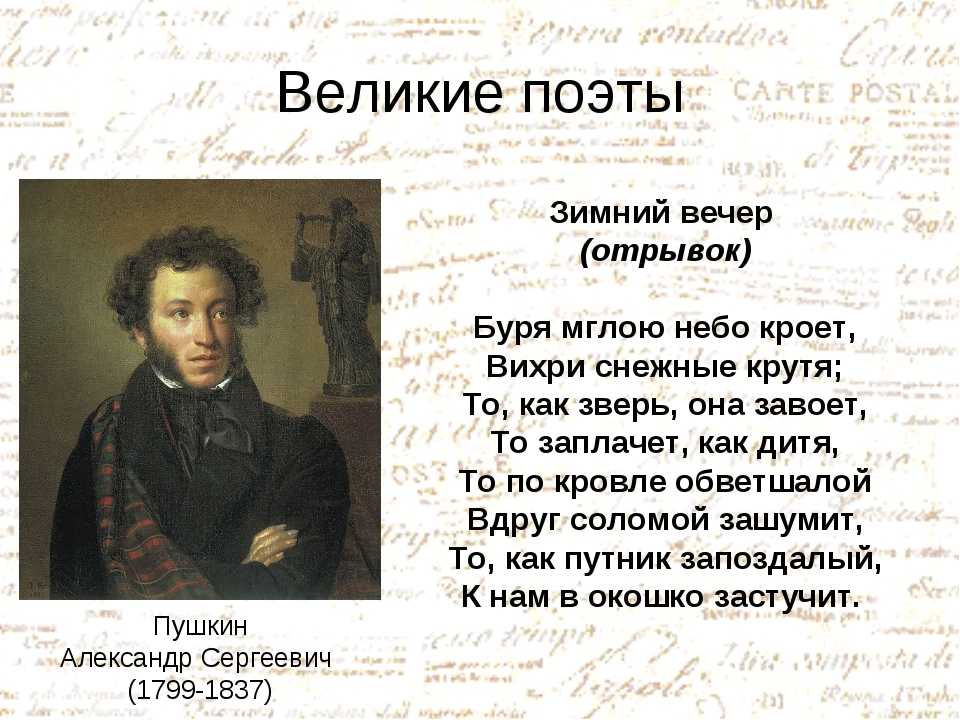

Хотя в повествовании «Капитанской дочки» много восхитительных поворотов, самыми сильными элементами являются его атмосфера и персонажи. Большая часть происходящего вызвана метелью, которая обрушивается на Петра, когда он и его слуга направляются к полковой заставе.

«Я приближался к месту назначения. Вокруг меня раскинулась дикая и унылая пустыня, изрезанная холмиками и глубокими оврагами. Все было засыпано снегом. Солнце садилось. Наша повозка ехала по узкой дороге, вернее, по тропе, оставленной санями крестьян. Вдруг мой шофер оглянулся и, обращаясь ко мне, —

— Сударь, — сказал он, сняв шапку, — не прикажете ли мне повернуть назад?

«Почему?»

«Погода неопределенная. Уже есть небольшой ветер. Разве ты не видишь, как метет снег на поверхности?

Уже есть небольшой ветер. Разве ты не видишь, как метет снег на поверхности?

«Ну какое это имеет значение?»

«А ты видишь, что там?» Возница указал кнутом на восток.

«Я ничего не вижу, кроме белой степи и ясного неба».

«Там, там; смотри, это облачко!»

Я действительно заметил на горизонте маленькое белое облачко, которое сначала принял за далекий холм. Мой водитель объяснил мне, что это облачко предвещает метель. Я слышал о снежных бурях, характерных для этих мест, и я знал, что целые караваны иногда были погребены под огромными снежными заносами. Савельич был того же мнения, что и кучер, и советовал мне повернуть назад, но ветер показался мне не очень сильным, и, надеясь успеть вовремя на ближайшую почтовую станцию, я велел ему постараться ехать скорее. Он пустил своих лошадей в галоп, непрестанно глядя, однако, на восток. Но ветер усиливался, облачко быстро поднималось вверх, становилось все больше и гуще и, наконец, закрыло все небо. Снег сначала начал падать мелко, но вскоре крупными хлопьями. Ветер свистел и выл; в мгновение серое небо потерялось в вихре снега, который ветер поднял с земли, скрывая все вокруг нас».

Ветер свистел и выл; в мгновение серое небо потерялось в вихре снега, который ветер поднял с земли, скрывая все вокруг нас».

Чтение этого очень простого, но сильного описания переносит читателя прямо в степь, дает ощущение необъятности русского пейзажа. Но дикое чудо этой сцены также является атмосферным отражением того, что будет происходить в истории, диких подавляющих действий восстания и возможного затишья, которое должно наступить.

Поразительное сходство в творчестве Пушкина с Толстым и даже Достоевским заключается в способности передать сложный мир природы, общества и общественно-политического положения точным, скупым, простым языком. И это заставляет вас понять, что лучший текст почти как алхимия: несколько деталей могут говорить о многом. Я нахожу, что большая часть современного письма делает как раз обратное: деталь за деталью передается в своего рода натиске, ничего не оставляя воображению. Целью может быть ясность, но конечным результатом, по иронии судьбы, является затемнение. Когда я достигаю этого момента, читая опубликованные или неопубликованные произведения, я ловлю себя на желании вернуться к чтению Пушкина. 9.

Когда я достигаю этого момента, читая опубликованные или неопубликованные произведения, я ловлю себя на желании вернуться к чтению Пушкина. 9.

Капитанская дочка Александра Пушкина

Всем привет! Угадайте, что я, наконец, смог закончить за последние несколько дней? … *барабанная дробь*… «Капитанская дочка» Александра Пушкина!

Я знаю, что уже давно не обещал вам рецензию, но по ряду причин я не мог дочитать книгу до сих пор.

Сама книга совсем не длинная, ее легко можно прочитать всего за несколько дней, и как я уже говорил в одном из своих предыдущих постов, причина, по которой я не смог ее закончить, заключалась в том, что я не на самом деле читая это, я прочитал первую главу, а затем остановился. Кстати, версия, которую я читал, была переведена на итальянский язык.

Что касается сюжета, то я не ожидала, насколько он может быть интересным и захватывающим, клянусь, в некоторых моментах мне просто не терпелось перевернуть страницу и узнать, что же произойдет дальше. Я был глубоко вложен в этих персонажей, чего я не ожидал, так как это всего лишь короткая книга.

Я был глубоко вложен в этих персонажей, чего я не ожидал, так как это всего лишь короткая книга.

Это исторический роман, действие которого происходит во время восстания Пугачева против Екатерины II во второй половине XVIII века. Главный герой, Петр Андреич Гринёв, знатный юноша, которого отец отправляет в армию, чтобы укрепить свой характер. Во время службы он знакомится с Машей, дочерью капитана Ивана Миронова, командира форта Белогорский, где он служит. Эти двое влюбляются друг в друга, и их история любви является главной темой всей истории. Все усложняется, когда мятежник Пугачев и его армия казаков атакуют Форт и в процессе умудряются убить родителей Маши.

Я не буду раскрывать концовку, если вам интересно, я настоятельно рекомендую вам прочитать ее, потому что я нашел ее очень интересной и убедительной. Я узнал немного больше о русской истории, и в книжном издании, которое мне досталось, есть еще один исторический роман, тоже Пушкина, под названием «История Пугачева», который я сейчас читаю. Это менее романтизированное и более историческое описание событий, приведших к пугачевскому бунту.

Это менее романтизированное и более историческое описание событий, приведших к пугачевскому бунту.

Это тоже была моя первая книга русского писателя Александра Пушкина. Мне было любопытно узнать, понравится ли мне его стиль или нет, и я должен сказать, что он мне очень, очень нравится. Я знаю, что он считается одним из величайших в русской литературе, как в Италии у нас есть Данте, в Англии есть Шекспир, а в России есть Пушкин, так что я знаю, что он был одним из великих. Я должен сказать, что я действительно наслаждаюсь своим путешествием по русской литературе, я еще не нашел ни одной книги, которая бы мне совсем не понравилась. Все они уникальны, загадочны и глубоки, на мой взгляд, и мне не терпится прочитать больше.

Вот сейчас читаю «Историю Пугачева» и роман Валерио Массимо Манфреди, итальянского автора, который называется «Тевтобурго», не знаю, как переведут название на английский, наверное : «Тейтербург». После этого у меня есть еще три книги русских писателей, «Пиковая дама» тоже Пушкина, «Шинель» и «Нос» Гоголя и «День опричника» Владимира Сорокина.

Leave A Comment